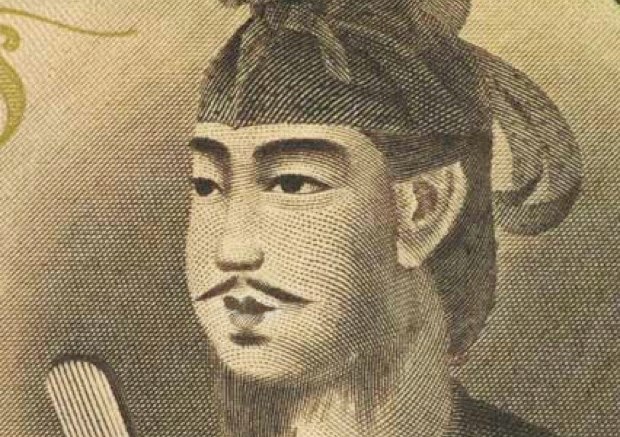

Prince Shotoku of Japan

When Prince Shotoku was born, Japan was not much more than a riverbank populated by barbarian hordes. By the time he died, though, Buddhism was the state religion, and the Golden Age had begun.

In the middle of the sixth century in Japan, the Imperial Court was, according to Peter Matthiesson in his book The Nine-Headed Dragon River, made up of nothing more than “rude assemblies” of people, without a government or written language, who’d arrived from the nearby mainland coasts and lived “in shifting settlements along the rivers.” Various clans battled for power at that time, and it was not uncommon for one clan member to murder another in order to rise to power. Prince Shotoku was born into this roiling culture in 574 C.E. His father and mother were the emperor and empress of the ruling Soga clan, which was struggling to keep hold of the throne.

Buddhism had come to Japan from the Korean kingdom of Paekche fifty-two years before, but it had not been embraced in any significant way. The prince’s great-uncle, though– despite being a bit of a barbarian himself–had become a student of Mahayana Buddhism during that time, and it was because of his influence that Prince Shotoku, as a young boy, began memorizing Buddhist texts. (The mythology of the young prince’s childhood includes the fact that he could talk by the time he was four months old, and read and write by his first birthday.)

When the prince’s father died (having declared himself a Buddhist after the prince installed himself by his bedside for days on end, praying for his recovery), the prince’s great-uncle had one of his own nephews killed in order to keep him from ascending the throne; according to some scholars, he wanted to insure that the prince, not old enough at the time, would someday rise to power and make Buddhism the state religion. In the meantime, the prince’s great-aunt was installed as empress, and within two years she made the prince her Regent and Crown Prince.

Because the Soga clan was still battling to stay in power, the prince prayed to the Four Buddhist Guardian Kings (the Shitenno), and promised them an official Imperial temple in their honor if they helped him end the strife in the region. As if in response, the head of the prince’s rival clan was killed in battle, and the Soga clan was able to finally secure its seat.

Keeping his word to the Guardian Kings, Shotoku began the construction on their temple, Shitenno-ji (Temple of the Shitenno), in 593. When that temple was finished he began construction of a second, in Nara, where he was born, which he called Horyu-ji. He built yet another temple near Osaka so that all those traveling in and out of Japan would pass through it, and another temple, Tenno-ji, which contained a college, a monastery, a hospital and an asylum. Tenno-ji became a model for future such complexes. Though the fact has been contested, many scholars say that Prince Shotoku built 45 temples in the Nara-Osaka region, most of which were not only used as religious centers, but also schools. During this time of temple building, Prince Shotoku began studying Buddhism under the guidance of two Korean monks.

Ten years after the prince took power, he issued what he called his Seventeen Article Constitution, which was not so much a legal document, as it was a moral treatise, based on Confucianism and Buddhism, which people regard as the foundation for Japanese culture today. The Constitution not only set down the guidelines for a centralized state like China’s, headed by a single ruler who would rise because of merit, not birth, but it also laid out suggestions for right conduct. For instance, according to Dr. Taitetsu Unno in his book River of Fire, River of Water, article ten of the Constitution stated, “Let us cease from wrath, and refrain from angry looks. Nor let us be resentful when others differ from us. For all men have heart, and each heart has its own leanings . . . for we are all, one with another, wise and foolish, like a ring which has no end . . .”

With the Constitution in place, the prince set out to enrich his country further by inviting scholars from both China and Korea to come to Japan and teach his people astronomy, geography, medicine and other sciences. Meanwhile, the prince became a scholar himself, writing commentaries and lecturing on the Lotus Sutra, the Lion’s Roar of Queen Shrimala Sutra, and the Vimalakirti Nirdesha Sutra. He also compiled a complete history of Japan, and developed social programs and public works like moats and roads for the benefit of his people. Having ushered in what historians refer to as a Golden Age in Japan, Shotoku died at the age of 49 in his sleep in 622 C.E.